WATER & POWER

Photography by Brandon Tauszik

Essay by Jenny Odell

Co-published in the Science History Institute

.

Print zine available here.

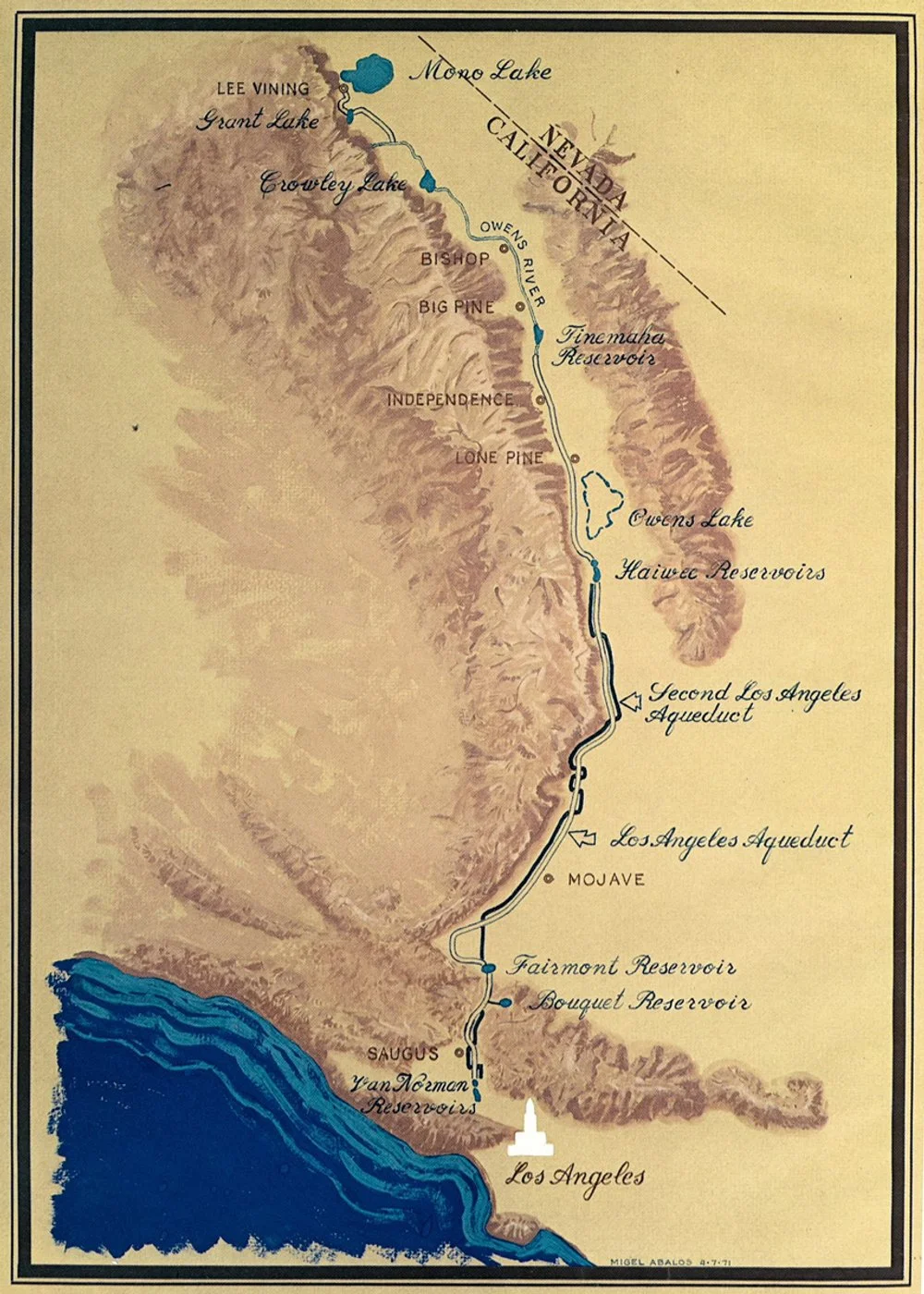

In the midst of Los Angeles, with its gardens and free-flowing water, you can forget how stacked the odds are there against human civilization. It seems given: There is a city, therefore there is water. To get a sense of what lies beneath and before all this, you’d have to drive to the nearest desert. And to get a sense of why it’s not like that, you’d have to visit the Owens River Valley, an arid wasteland created when the growing city of Los Angeles decided in 1905 to suck it dry from more than 200 miles away. Between here and there are countless structures that instantly dispel any given-ness one feels from within the city: the monumental, rusted pipes transporting Sierran snowmelt; the concrete channels across cracked, creosote-studded earth; the 100-year old hydroelectric power plants full of esoteric dials and gauges, running the water through turbines. Pretty soon, the correct sequence reveals itself: There is water — which we went to extraordinary lengths to move — therefore there is a city.

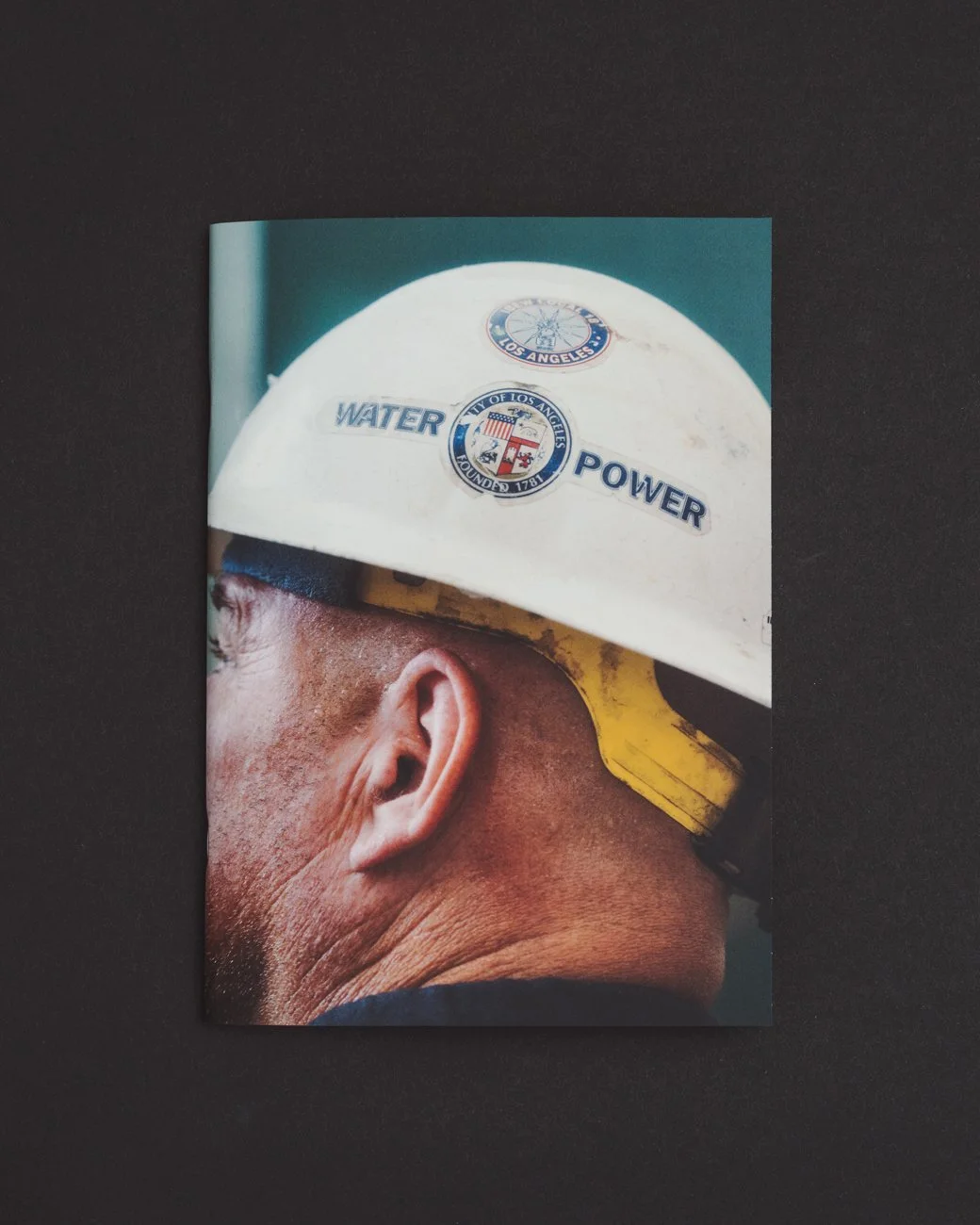

Any visual consideration of this sprawling system inspires contradictory feelings. There’s the sheer rapaciousness of it, the story of humans exhausting resources on a grand scale — but then there’s the grand scale itself, with all its associated feats of design, engineering, and ingenuity. There’s the solid monumentality of the industrial shapes — but also the unsettling contingency of the whole thing, the feeling of a crazy bet. In the 1910s, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power used the movement of water to build the aqueduct itself, building power plants along streams to generate the electricity that made cement, dredged canals, powered drills, and ferried equipment and workers. The rest of the power came from humans and mules, digging trenches and hauling enormous pipes into place. “That was back when labor was labor,” one worker at the Big Pine Power Plant tells Brandon Tauszik, the photographer. “It was backbreaking. It shortened your life by 50 percent. And you felt it at the end of the day.”

When Tauszik looked for photographs of the L.A. hydroelectric system, the most recent ones he found were from around 100 years ago, when it was all relatively new. His own images, echoing the formal style of those earlier ones, capture a strange bifurcation in time: the machines have remained the same — so much that one worker calls his stream-side power plant a “working museum” — but the present they inhabit has changed. The photos are in color, the population of L.A. has multiplied by an order of ten, and it’s drier out there in the desert. The question of water and power looms with a different kind of urgency from before. In this context, Tauszik’s photographs perform their own kind of maintenance on the system, keeping the conduit open between the public imagination and these otherwise forgotten sites.